Conserving a WWII Japanese Katana

Above: Japanese Officer’s Katana, Devil’s Porridge Museum (before treatment)

This beautiful sword, which belongs to the collections at the Devil’s Porridge (DVP) Museum, was surrendered to Dr. Lockhart Frain-Bell in Burma when the Japanese surrendered at the end of the Second World War. Bell was posted in Burma with the Royal Army Medical Corps in 1944, serving for the 82nd West African Frontier Force. The sword was then donated to the DVP Museum in 2022 by Anne Frain-Bell, wife to the late Dr. Frain-Bell.

The sword is titled as munitions grade, meaning that it would have been issued to an officer during the war as a status symbol, and has Gunto mountings, which indicates that it would have been worn hanging from the hip as opposed to being tucked into a belt.

With a steel Nagasa (blade), and a Tsuka (hilt) made of wood and covered with Same-kawa (shagreen) with a traditional Ito (hilt wrap) made of cotton, the sword is highly decorated, with Sakura (cherry blossom) flowers on the Menuki (decorative grip - underneath the Ito), the Kashira (pommel), and the Tsuba (hand guard), which is Aoi-gata shaped (below right)

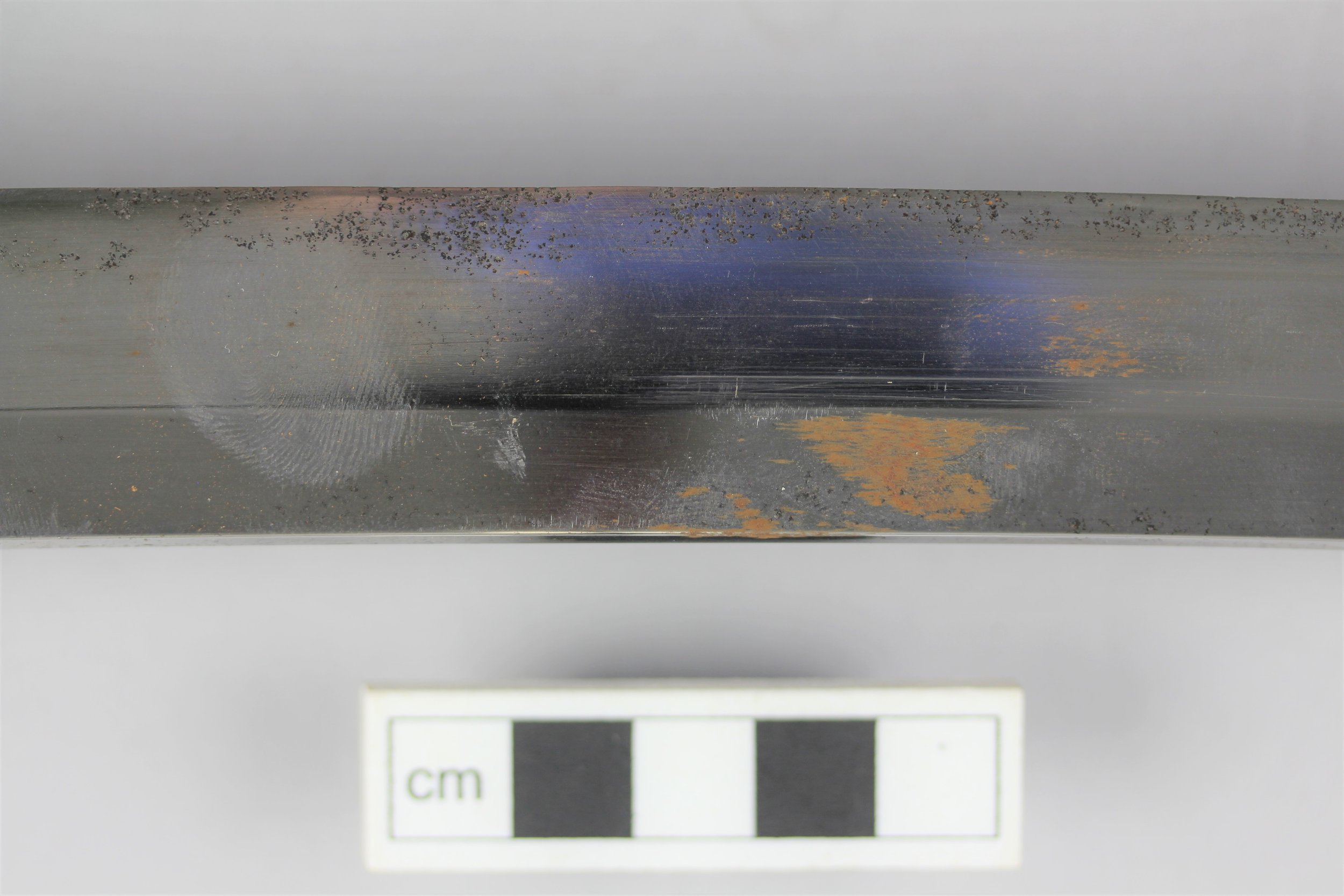

When the Katana came to AOC it was suffering from various condition issues. The Nagasa, as seen in the image at the top and the image below (second on the right) was suffering from flash rusting, where fingerprints had stared to corrode. Some of the cuprous metal components were beginning to corrode as well, with green-blue corrosion products visible on the decorative opening of the Saya (scabbard), and on the Sakura flowers of the Menuki and Kashira. The leather wrapping on the Saya was heavily soiled, as were the placoid scales of the Same-kawa on the hilt, which were also in need of consolidation, as they had already suffered numerous losses (below, far right and far left). Additionally, the Tsuka, Tsuba, and Seppas (decorative washers on either side of the Tsuba) were all very loose due to misplacement of the Mekugi peg.

……….I certainly had my work cut out for me!

The first step in the treatment was the removal of the Tsuka so that all the components could be assessed and individually cleaned, and the Nakago (tang) beneath could be assessed. In order to do this, the Katana was secured to the work bench, and the Mekugi peg gently tapped loose using a chop stick, allowing for the Tsuka, Tsuba, and Seppas to all be removed.

Following removal of these components, it was found that the Nakago had severely corroded, and the corrosion had deposited onto the other components causing significant damage (see below left). However, beneath the corrosion it was still possible to see most of the inscription on the Nakago (see further down) - an exciting discovery! Japanese swordsmiths traditionally inscribed a makers mark, or signature, called the Mei, on the Nakago of a blade, which can sometimes allow for the maker of the sword to be identified. In order to better document this inscription, we used in-house Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) technology to create a record, which will be passed on to the DVP Museum for future interpretation.

Corrosion was then reduced from Tsuba and Seppas using hand tools, allowing for further inscriptions to be revealed; only the loose, powdery corrosion was removed from the Nakago however, as it is traditional to allow this part of the Katana to corrode with age.

Above: Tsuba & Seppas, before treatment (left) and after treatment (right)

Above: Detail of the inscription found on the Nakago, following removal of the Tsuka (before treatment)

Above: Detail of the inscription found on the Nakago (after treatment)

Next the corrosion on the cuprous components of the Saya and Kashira, and the Menuki hand grip, was reduced using hand tools and solvent swabs. The soiling on the Saya was also reduced, as was the soiling on the placoid scales of the Same-kawa on the Tsuka; the scales were then consolidated using 4% Klucel G in ethanol to prevent any further losses.

Above: Treatment of the placoid scales (left), before treatment (centre) and after treatment (right)

Finally, the Nagasa was treated to reduce the flash rusting and remove the fingerprints; first using acetone to remove a suspected previous coating, the corrosion and fingerprints were then reduced using a calcium carbonate precipitate. The Nagasa was then polished using a traditional sword polishing kit, recommended through consultation with a professionally trained Japanese Sword restorer.

This kit consisted of a red powder ball containing Uchiko, a very fine abrasive powder; this ball is lightly tapped on the blade to release the powder, which is then carefully polished off using rice paper (see below). After the blade was polished, it was lightly oiled with Choji oil, a traditional oil used for preserving Japanese blades that consists of mineral oil mixed with clove oil (1-10%). The oil was applied to the blade, and the tang, of the sword using a clean lint free cloth.

The sword was then ready to be reassembled; the Tsuka, Tsuba, and Seppas, were replaced over the Nakago, and the Mekugi peg gently tapped into place. Removal of the loose corrosion allowed for a more secure placement of the Tsuka and Mekugi peg, which significantly reduced the movement of the Tsuba on the Nakago.

The sword is now complete (see below) and ready to be returned to the Devil’s Porridge Museum in Eastriggs, where curator Rebecca Short is planning an exhibition over the course of the next year.

For more information on the Devil’s Porridge Museum, head to Home - The Devil's Porridge Museum (devilsporridge.org.uk)

Above: Japanese Officer’s Katana, Devil’s Porridge Museum, (after treatment)