Grand Redesigns: a History of Remodelling at Dunbeath Broch

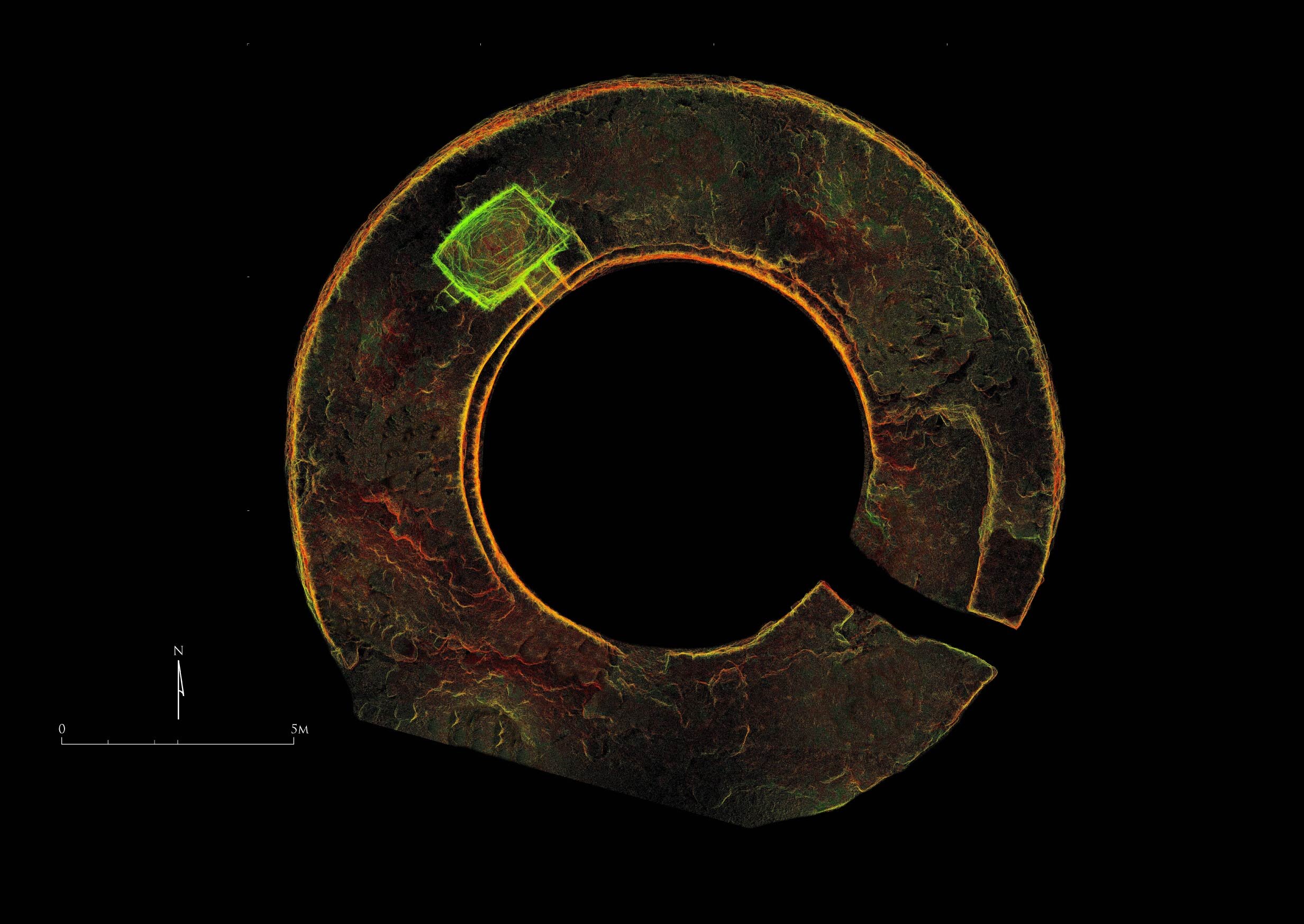

Dunbeath Broch is located on a prominent spur of land overlooking Dunbeath Water – an impressive setting which would have afforded the site commanding views down the strath when the broch was in use. The broch was excavated in the 19th century, and was repaired and consolidated under archaeological supervision in 1990. However, in recent years, vegetation and tree growth on and around the monument, as well as increasingly unstable stonework, has become a source of concern for the long-term integrity of the broch. Dunbeath Community Council was awarded an Ancient Monuments Grant by Historic Environment Scotland to develop a management plan. The Council aims to improve on-site interpretation and to promote the broch as a visitor attraction; recent improvement works to the footpath leading to the monument mark the first steps on this journey. In May 2016 AOC was commissioned to carry out a structural survey and management assessment of the site.

The broch first came to antiquarian attention in 1866, when W S T Sinclair of Dunbeath emptied the interior of rubble. This was one of the earliest antiquarian investigations of any broch in Caithness, but the works were extensive, clearing the interior and the external wall faces of the broch of rubble, revealing the entrance, a guard cell and a small intra-mural gallery in the north-west. Relatively few artefacts were recovered during the excavations: a large quantity of animal bone, a possible human vertebra, some coarse stone implements and a small iron spearhead. At some point following the 1866 excavations, limited rebuilding was carried out, including reinstatement of the intra-mural cell in the western side of the monument. It appears that this work was relatively crudely done, and the resulting stonework was considered unsafe and a danger to visitors. A drystone dyke was erected around the broch to form a small enclosure; this was presumably carried out shortly after the excavation and is shown on the first edition Ordnance Survey map of 1877.

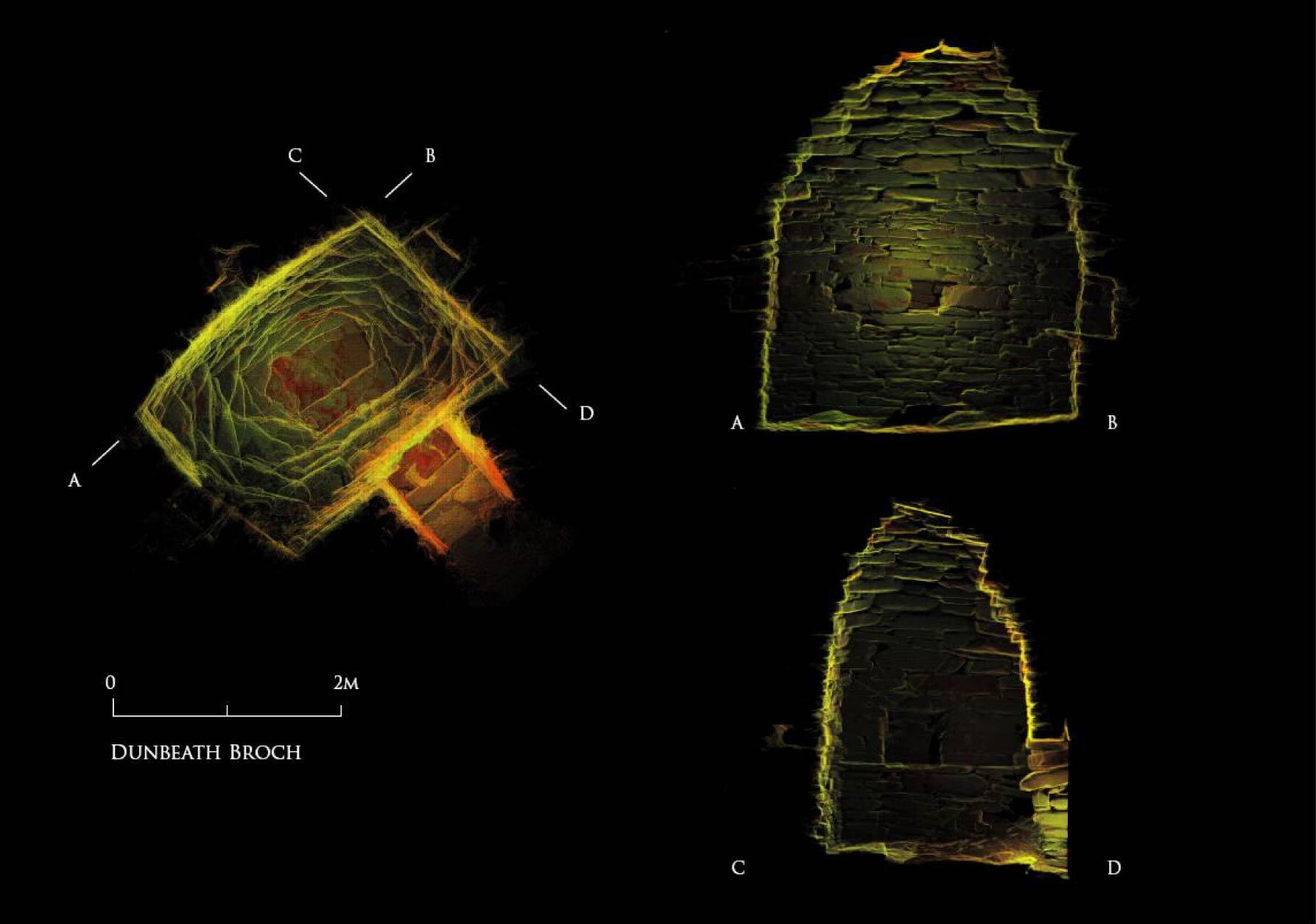

No further work was carried out until over a century later, when in 1990 archaeologists from the University of Glasgow supervised a programme of consolation and repair. Vegetation was cleared and trees removed, and loose rubble and debris was cleared from the entrance and the interior. The corbelled roof of the intra-mural cell, which had apparently been completed during the 19th century rebuilding, was stripped down and rebuilt to make the structure safer for visitors. At this time large sections of the inner wall face were repaired with new stonework, the scarcement ledge was repaired and sections of the upper wallhead rebuilt. This work was competently executed, but detailed records of which areas were rebuilt, and to what extent, are missing from the site archive and discerning original from modern stonework is difficult.

Careful analysis of the structure itself and the survey data has revealed that the broch has a long history of rebuilding and remodelling: while the original broch was probably built in the early or middle Iron Age, the tower suffered a catastrophic collapse in antiquity (perhaps during the later Iron Age), necessitating the near-complete rebuilding of the southern half of the monument; also, the intra-mural cell is unlikely to have been an original feature and was probably added in the first century BC/AD.

AOC undertook 3D topographic survey in conjunction with the structural assessment and appraisal. A Faro Focus 3D laser scanner was used to collect a high-resolution pointcloud dataset encompassing all of the exterior areas of the broch, as well as the interior of the intra-mural cell. A detailed photographic record was compiled, and a photogrammetric model created from over 400 photographs. The resulting archive provides a highly accurate and detailed archive of the condition of the monument at the time of the survey, and can be used as the baseline for any future conservation works.

Work at Dunbeath Broch was carried out on behalf of Dunbeath Community Council, and was supported by funding from Historic Environment Scotland.